One aspect of SSL which many people are not aware of is that SSL is capable of compressing the entire SSL stream. The authors of SSL knew that if you’re going to encrypt data, you need to compress it before you encrypt it, since well-encrypted data tends to look pretty random and non-compressible. But even though SSL supports compression, no browsers support it. Except Chrome 6 & later.

Generally, stream-level compression at the SSL layer is not ideal. Since SSL doesn’t know what data it is transporting, and it could be transporting data which is already compressed, such as a JPG file, or GZIP content from your web site. And double-compression is a waste of time. Because of this, historically, no browsers compressed at the SSL layer – we all felt certain that our good brothers on the server side would solve this problem better, with more optimal compression.

But it turns out we were wrong. The compression battle has been waging for 15 years now, and it is still not over. Attendees of the Velocity conference each year lament that more than a third of the web’s compressible content remains uncompressed today.

When we started work on SPDY last year, we investigated what it would take to make SSL fast, and we noticed something odd. It seemed that the SSL sites we tested (and these were common, Fortune-500 companies) often were not compressing the content from their web servers in SSL mode! So we asked the Web Metrics team to break-out compression statistics for SSL sites as opposed to unsecure HTTP sites. Sure enough, they confirmed what we had noticed anecdotally – a whopping 56% of content from secure web servers that could be compressed was sent uncompressed!

Saddened and dismayed, the protocol team at Chromium decided to reverse a decade long trend, and Chrome became the first browser to negotiate compression with SSL servers. We still recognize that compression at the application (HTTP) layer would be better. But with less than half of compressible SSL content being compressed, optimizing for the minority seems like the wrong choice.

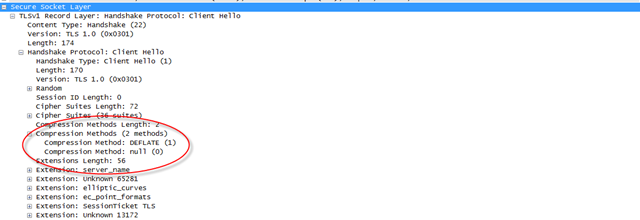

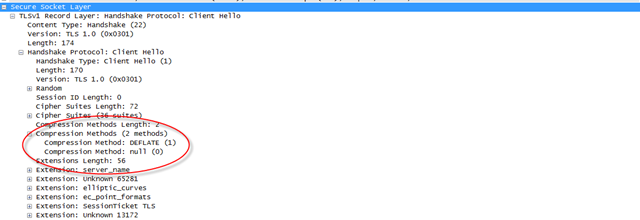

So how do you know if your browser compresses content over SSL? It’s not for the faint of heart. All it takes is your friendly neighborhood packet tracer, and a little knowledge of the SSL protocol. Both the client and the server must agree to use compression. So if a server doesn’t want to use it (because it may be smart enough to compress at the application layer already), that is no problem. But, if your server uses recent OpenSSL libraries, it can. And you can detect this by looking at the SSL “Client Hello†message. This is the first message sent from the client after the TCP connection is established. Here is an example from Chrome, viewed with Wireshark.

So, does this help? Sites that use compression at the application layer don’t need this, and it has no effect (those are in the minority). For servers that opt out, it has no effect. But for servers that opt in, HTTP headers do get compressed a little better, and any uncompressed data stream gets compressed much better.

I did find that https://www.apache.org/ is a showcase example for my cause. Apache.org runs a modern SSL stack and advertises compression support on the server, but they forgot to compress jquery.js. If you load this site with Chrome, you’ll only download 77,128 bytes of data. If you use IE8 (firefox will be similar), you’ll download 146,595 bytes of data. Most of this difference is just plain old compression.

For the 50% of site owners out there that can’t configure their servers to do compression properly, don’t feel too bad – even apache.org can’t get it right! (Sorry Apache, we still love you, but can we turn mod_gzip on by default now? 🙂